|

|---|

| Download the PDF version |

Housing is a human right (PDF), enshrined in the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, signed and ratified by Canada.1 And yet, many Canadians do not have access to housing (PDF) they need at a cost they can afford.2 Executing affordable housing is contingent on three pillars: money to finance, land to build, and organizational capacity to action.

This paper expands on the workshop session Financing, Land and Organizational Capacity: Affordable Housing Development that took place in Ottawa, on April 26, 2018 at the Canadian Housing and Renewal Association’s annual Congress on Housing and Homelessness.

Session panelists included Howie Wong, CEO of Housing Services Corporation in Ontario who discussed the lack of long-term financing as a gap to developing affordable housing; Kit Hickey, Executive Director of Housing Alternatives Inc. and Rehabitat Inc. in New Brunswick who illustrated how land banks may be used as a tool to promote the development of affordable housing; and Graeme Hussey, Development Manager at the Centertown Citizens Ottawa Corporation and President of Cahdco, presented ways in which non-profit organizations can organize, fund, and support affordable housing development. The session was moderated by Kaye Melliship, Executive Director of the Greater Victoria Housing Society.

Paper by Ayda Agha, MSc. Community Health, Ph.D. Candidate Experimental Psychology, University of Ottawa & Konrad Czechowski, M.A. Experimental Psychology, Ph.D. Candidate Clinical Psychology, University of Ottawa

Affordable Housing – A Global Challenge

Access to suitable, affordable, and adequate housing is fundamental to individual and community health, well-being and prosperity, as well as the foundation for healthy economies and thriving communities. Yet globally, in both developing and advanced economies, cities are struggling to meet the challenges of providing housing for not only their poorest citizens, but low and middle-income populations as well.3

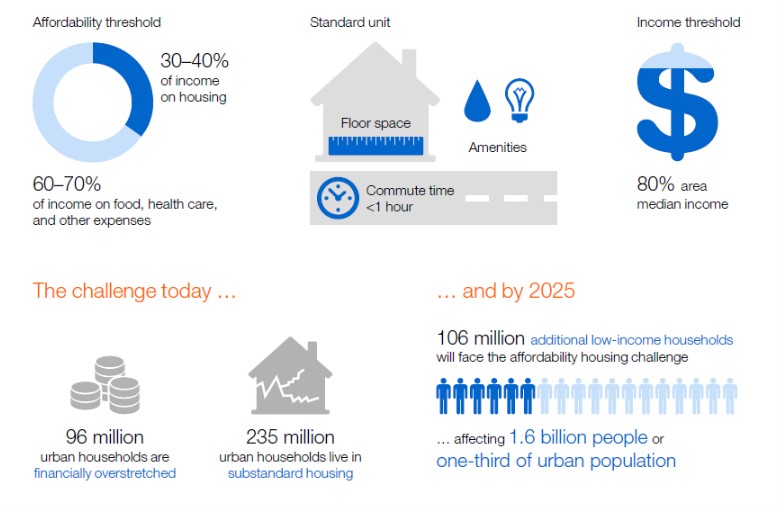

In 2014 the McKinsey Global Institute published A Blueprint for Addressing the Global Affordable Housing Challenge. According to the report, an estimated 30 million urban households around the world live in substandard or unaffordable housing. Further, approximately 200 million households in the developing world live in slums. The issue persists in the developed world, where in the United States, European Union, Japan, and Australia, more than 60 million households are financially overextended by housing costs. Figure 1 illustrates the extent of the affordable housing crisis on a global scale.

|

|---|

| Figure 1: the affordable housing challenge worldwide |

Current trends in global urban migration and income growth suggest that by 2025, an estimated 440 million urban households, amounting to 1.6 billion people, will occupy crowded, inadequate, and unsafe housing or live in housing that costs beyond their means of affordability.

The Need for Affordable Housing in Canada

Affordable housing in Canada does not only include housing that is subsidized by the government. The term is broadly applied to housing provided by the private, public and non-profit sector, and includes a variety of temporary and permanent housing that have affordable rental and home ownership options.4

Measuring affordability involves comparing the cost of housing to a household’s ability to meet that cost. A common measure utilized is the shelter-cost-to-income ratio (PDF).5 This refers to the proportion of average total income a household spends on shelter costs.6 The Canadian Government deems housing affordable when the shelter cost-to-income ratio is below 30%. If a household falls below adequacy, suitability, or affordability (falls below the 30% threshold) standards, it is considered to be in core housing need.

According to the 2016 census, nearly 1.7 million households in Canada are considered in core housing need, amounting to a rate of 12% nationally; with rates approaching as much as 20% in certain cities such as Toronto or Vancouver.7

An estimated 235,000 individuals experience homelessness in a year (PDF), with certain groups overrepresented in this population including youth, veterans, and Indigenous Peoples.8 Middle-income families are also struggling with the housing affordability crisis. There has been serious deterioration of middle-income housing ownership (PDF) in Canada between 2000-2015, as the price of houses has grown at a rate nearly three times that of household income, coupled with exceedingly high interest rates.9

The problem does not subside for renters, where many Canadians are spending more than 40-50 per cent of their incomes on rent and utilities.10

Unfortunately, many Canadians do not have access to housing they need at a cost they can afford. This has considerable consequences for the health of Canadians. Availability of affordable housing contributes to social determinants of health (PDF). Experiencing housing insecurity during childhood and adulthood has significant negative heath impacts on individuals and families.11

Housing affordability and instability, including homelessness, or living in poor quality housing and neighbourhoods, are associated with a range of poor mental and physical health outcomes (PDF).12

As a response to this urgent need, the Government of Canada launched the National Housing Strategy (NHS) in 2017 to address affordable housing in Canada.13 The NHS is a 10-year plan, dedicating $40 billion to the goal of making sure Canadians across the country can access housing that meets their needs, including investments in more affordable, accessible, inclusive and sustainable housing.

Fixing the Global Challenge

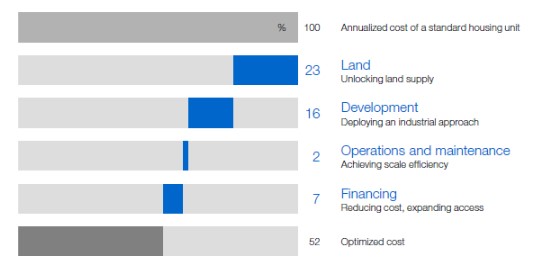

To address the growing global housing crisis, the 2014 McKinsey Blueprint report outlined four approaches – through land, development, operations and management, and financing – that could reduce the cost of housing substantially and narrow the affordable housing gap, see Figure 2.

|

|---|

| Figure 2: four levers that can address the global affordable housing challenge |

Land: Unlocking Land Supply

Land is the largest expense in real-estate. Securing land in appropriate locations can be the most effective way to reduce costs. In many of the largest global cities, there are several parcels of land that are unoccupied or underused. Land could be unlocked for the development of affordable housing through measures such as transit-oriented development, idle-land policies, release of public land, and inclusionary zoning.

Governments often own significant shares of land in urban areas that are unused or undeveloped and are frequently valued below market prices; this kind of land could be released or sold. Moreover, government policies can put in place incentives for private developers to provide land for affordable units, such as increasing the size of plot land permitted.

Development: Reduction of Construction Costs

Despite progress made in manufacturing industries, productivity in the construction industry has stagnated or even decreased in many countries. There is potential to reduce project costs and completion times by up to 30-40 per cent if developers incorporate capital productivity and value engineering measures. These include design-to-value techniques, whereby unnecessary costs are reduced by standardizing and de-specifying building requirements, for instance, by reducing ceiling heights or using less costly materials or incorporating industrial approaches, such as assembling buildings from prefabricated components manufactured off-site.

Standardization can also help foster efficient procurement methods and process improvements, since it simplifies training and productivity as workers gain expertise with the same tasks and products. Further, standardization can help manage suppliers and cost of materials, such as buying in bulk at discounted value.

Improved Operations and Maintenance

Improving energy-efficiency by using energy-saving materials in insulation, windows, and heating and cooling are ways to cut costs. Programs exist at all government levels that provide subsidies to low-income households or to housing located in low-income areas to utilize energy-efficiency retrofits.

Reducing maintenance costs and improving asset management can make housing more affordable. Establishing the right standards and governance can avoid the deterioration of properties as well as help preserve asset values. Maintenance expenses can be reduced by helping property owners find qualified suppliers, through registration and licensing, and by consolidated purchasing and pooling demand for services.

Financing: Lowering Financing Costs for Buyers and Developers

How housing is financed has a significant impact on affordability for both home buyers and developers. Reducing borrowing costs to buyers and assisting in developer financing can help reduce the housing affordability gap. This can be accomplished by improving access to finance for low-income households by reducing the cost of mortgage funding and the risk of lending, as well as leveraging collective saving.

Contractual savings programs that create pooled savings can help low-income buyers with down payments, so they can finance purchases with smaller, less risky loans. These programs can also provide capital for low-interest rates on mortgages. Governments can help cut financing costs for developers by making affordable housing projects less risky by guaranteeing buyers or tenants for finished units. Additionally, better rental options are needed for low-income households as an alternative to ownership.

Addressing Affordable Housing in Canada

Despite government initiatives, closing the affordable housing gap in Canada requires cooperation and partnerships across sectors. In 2015 the Business Transformation: Promising Practices for Social and Affordable Housing in Canada (PDF) feasibility study was conducted by Housing Partnership Canada and other stakeholders to assess the scope and need for affordable housing providers across Canada.14 The study found that the estimated total Canadian capital requirement for the next 10 years ranged from $77 billion to $121 billion. The findings confirmed the demand for housing capital that significantly exceeds government funding capacity by billions each year.

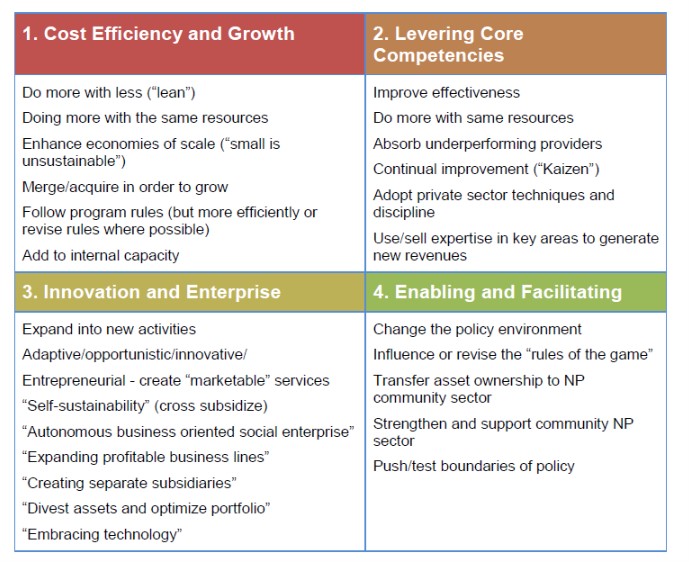

The study also explored emerging new business practices and innovation in Canada’s social housing system to better understand how sector-based solutions could foster the long-term sustainability of social housing assets. Some of the strategies discussed in that study are outlined in Figure 3.

One key finding is that many non-profit housing providers have merged their traditional social service programmatic functions with more entrepreneurial, revenue-generating activities through collaboration with other organizations and agencies. The study recommendations included: working towards cost efficiency and growth such as reducing and reusing resources; adding to internal capacity to improve, strengthen and support the community non-profit agencies; adopting private sector techniques; and innovating and expanding to new activities and sectors.

|

|---|

| Figure 3: business transformation strategies for affordable housing development |

These findings coincide with the approaches in the McKinsey Blueprint report that are also largely market-orientated solutions that aim to lower the cost of land, construction, operations and maintenance, as well as financing. Taken together, fostering affordable housing in Canada is contingent on three pillars: access to financing and capital, securing land to build, and developing the organizational capacity to execute.

Financing Canada’s Affordable Housing Needs

Canada is facing significant capital need to create affordable housing and replace the existing deteriorating social housing stock. The lack of access to long-term financing is a significant challenge in Canada, and refinancing loans come with great risks. With an ageing infrastructure, uneven government funding, and billions in funding required to fill the demand for affordable housing, there is need for more efficient and entrepreneurial use of assets.

To address the growing gap in capital funding, Housing Partnership Canada recommended the development of a dedicated sector bank, which resulted in the creation of the Housing Investment Corporation (HIC), a Canadian lending institution dedicated to the affordable housing sector. The organization was launched in early 2018 by Housing Partnership Canada, alongside founding partners BC Housing, Manitoba Housing, and Housing Services Corporation in Ontario, with the goal of building affordable housing in Canada.

Buyers and developers face challenges in accruing capital funding for various affordable housing projects. One way to get support in the private sector is through organizations that help housing providers aggregate their needs and provide them with necessary supports to accessing capital.

The HIC’s business model is simple. The borrowing needs of participating housing providers across Canada are aggregated and funding is provided for those needs through the Canadian debt capital market, offering providers access to unsecured, fixed low-cost, long-term financing.

This ties into the recommendations made by the McKinsey Blueprint report highlighting the need for programs that improve access to finance by reducing the cost of mortgage funding and the risk of lending, as well as leveraging collective saving. Overall, HIC’s goal is to offer better financing solutions in a way where the needs of housing providers and the financial capital market are gathered and negotiated together.

The HIC was modeled on past successful market precedents such as the Toronto Community Housing Corporation, the First Nations Finance Authority, and the Housing Finance Corporation in the United Kingdom. HIC is currently working on the first tranche of take-out15 financing expected to close in fall 2018. Initial funding of $20 million came from the federal Affordable Housing Innovation Fund and $2.5 million from three of the founding partners, leveraging into $200 million of lending capacity. Additional outreach efforts are currently underway targeted at housing providers with development plans or in the construction phase of development.

Financing Land – Community Land Banks

Accessing and securing property and land is the largest expense in real-estate. High land costs are the key reason why housing development is not economically feasible in large cities. Land costs (PDF) could be reduced by acquiring properties with ageing infrastructure or surplus land that is unoccupied or unused, for future housing or community development.16

A Community Land Bank is one way to accomplish this objective.

A Land Bank is a tool to acquire properties that are in an acute state of decline, often with rundown or neglected structures on them, that contribute to the lowering investment value of the surrounding community. The Land Bank repositions these properties for different uses and returns them to a productive state.

This includes houses, vacant lots and other undervalued properties and transforms them for a proposed use often determined by the community. The land is commonly acquired through tax foreclosures, land transfer, and donations. Once a property comes into ownership of the Land Bank it clears title and taxes owed.

More importantly, Land Banks generally do not retain ownership of the property. The property is sold or transferred to a new owner who has proposed a new use compatible with a community plan, creating any space deemed necessary by the community such as green spaces, parking lots, or affordable housing. When successful, Land Banks are ways to stabilize the decline of an urban area or neighbourhood, while simultaneously increasing the overall supply of affordable housing, green spaces, and community pride.

|

Land Banks offer a solution to communities that suffer from a saturation of neglected properties. A Land Bank demonstration project in Saint John, New Brunswick is currently underway that is supporting the development of affordable housing units in a low-income neighbourhood. The demonstration project looked to the United States as an example, where Land Banks have been used across many different communities for a number of years. Saint John has experienced a high rate of poverty for a number of years and maintains low conditions of housing stock. Further, the area has some of the oldest homes in the country that have been deteriorating for years. This makes the area an excellent candidate for a demonstration project to intervene with a land bank.

Current streetscape |

Land Banks are increasingly sprouting across Canada, having looked at the United States as a successful model approach. Through the Neighborhood Stabilization Program17 the United States government has used land banking as a strategy to assemble, temporarily manage, repurpose, and then dispose of vacant land in an aim to stabilize neighbourhoods in decline and encourage the reuse of property. With over 75 communities operating a formal land bank (PDF), the Neighborhood Stabilization Program importantly puts an emphasis on community participation and engagement, granting neighbours a formal voice on policy and operations decisions.18

Building Organizational Capacity

Despite progress, building affordable housing continues to be a challenge with little development in Canada. Provincial governments have been dealing with affordable housing in a manner that puts little risk on government and more on the agencies that provide services.

As a result, many not-for-profit organizations are looking at ways of becoming more self-sustaining and less reliant on government sources of funding. However, most not-for-profit and co-op providers of affordable housing are relatively small in scale and often do not have land or capacity to borrow money. In addressing these challenges (PDF) organizations have shared resources, pooled investment funds, and established new networks that enable collaboration and partnerships.19

|

Planned streetscape What are the aims of this project?The Saint John Land Bank project will help address the need for affordable and adquate housing in the old north end, one of the city’s low-income neighbourhoods. It will support the develoment of Victoria Commons into 47 mixed-income housing units, creating a combination of non-profit and co-operative rental housing. The findings from this initiative will inform the Saint John Land Bank’s goal of developing affordable housing in other priority neighbourhoods. The project ultimately aims to bring these units back to productive use, creating a solution for the community presently living among deteriorating properties. |

In the non-profit sector, organizational capacity building (PDF) seeks to strengthen the ability of an organization or agency to achieve a desired outcome by supporting their initiatives to build and access the skills, infrastructure, and resources required to achieve their mission.20

Recommendations from the 2015 HPC Business Transformation study emphasize successful organizations in the housing sector are looking at alternative ways to build capacity, such as renewing focus on cost efficiency and growth, leveraging leadership competencies, emphasizing innovation and enterprise, and enabling and facilitating a strong non-profit sector.

In Summary

This paper expands on the ideas and initiatives highlighted at the workshop session ‘Financing, Land and Organizational Capacity: Affordable Housing Development’ at the Canadian Housing and Renewal Association’s annual Congress on Housing and Homelessness in April 2018.

By exploring innovative strategies, housing providers and non-for-profit organizations are implementing new solutions in addressing challenges and barriers to foster affordable housing development and management.

Affordable housing is as much a global challenge as it is a challenge in Canada. Fostering affordable housing in Canada is contingent on three pillars: access to financing and capital, securing land to build, and developing the organizational capacity to execute.

Common themes arise in fostering affordable housing innovation, such as the value of cooperation and partnership and supporting community-led and community-based projects. In accessing financing and capital, strategies exist that aggregate the needs of affordable housing organizations and agencies by developing lending institutions and respond to an ever-present obstacle in affordable housing development. To secure land to build, Land Banks have sprouted throughout Canada as a means of developing affordable housing in close consultation with local communities. Last, to build capacity, organizations are sharing resources, pooling investment funds and establishing new networks by which to collaboration and foster affordable housing.

Endnotes

1. The Right to Adequate Housing: Fact Sheet N°21 (PDF). Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (2014).

2. Stephen Gaetz et al. The State of Homelessness in Canada 2016 (PDF). Canadian Observatory on Homelessness (2016).

3. A Blueprint for Addressing the Global Affordable Housing Challenge. McKinsey Global Institute (2014).

4. About Affordable Housing in Canada. Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (2018).

5. Willa Rea et al. “The dynamics of housing affordability (PDF).” Perspectives on Labour and Income 20, no. 1 (2008): 37-48.

6. Shelter-Cost-to-Income Ratio. Statistics Canada (2017).

7. Core Housing Need. 2016 Census, Statistics Canada (2017).

8. Stephen Gaetz et al. The State of Homelessness in Canada 2016 (PDF). Canadian Observatory on Homelessness (2016).

9. Wendall Cox and Ailin He. Canada’s middle-income affordability crisis. The Frontier Centre for Public Policy (2016).

10. M. Nahiduzzaman. Finding an Affordable Housing Option: Social Business as the ‘New’ Policy Tool? University of Regina and University of Saskatchewan (2017).

11. Toba Bryant. “The current state of housing in Canada as a social determinant of health. (PDF)” Policy Options, 24.3 (2003): 52-56.

12. Linda Wood. Housing and Health: Unlocking Opportunity (PDF). Toronto Public Health (2016).

13. A Place to Call Home: The National Housing Strategy. Government of Canada (2017).

14. Business Transformation: Promising Practices for Social and Affordable Housing in Canada (PDF). Housing Partnership Canada (2015).

15. Take-out financing is a banking term for paying off a lender to take sole and complete charge on a collateral. Take-out commitments are common in construction and development loans where long-term financing replaces short-term or bridge loans.

16. Jill Black. The Financing and Economics of Affordable Housing Development: Incentives and Disincentives to Private-Sector Participation (PDF). Cities Centre, University of Toronto (2014)

17. Neighborhood Stabilization Program. US Department of Housing and Urban Development (2018).

18. NSP Land Banking 101: What is a Land Bank? (PDF). US Department of Housing and Urban Development (2010).

19. Jana Svedova. Approaches to Financially Sustainable Provision of Affordable Housing by Not-for-profit Organizations and Co-operatives: Perspectives from Canada, the USA, and Europe (PDF). Centre for Sustainability and Social Innovation for BALTA (2009).

20. Caroline Claussen. Capacity Building for Organizational Effectiveness (PDF). United Way of Calgary and Area (2011).